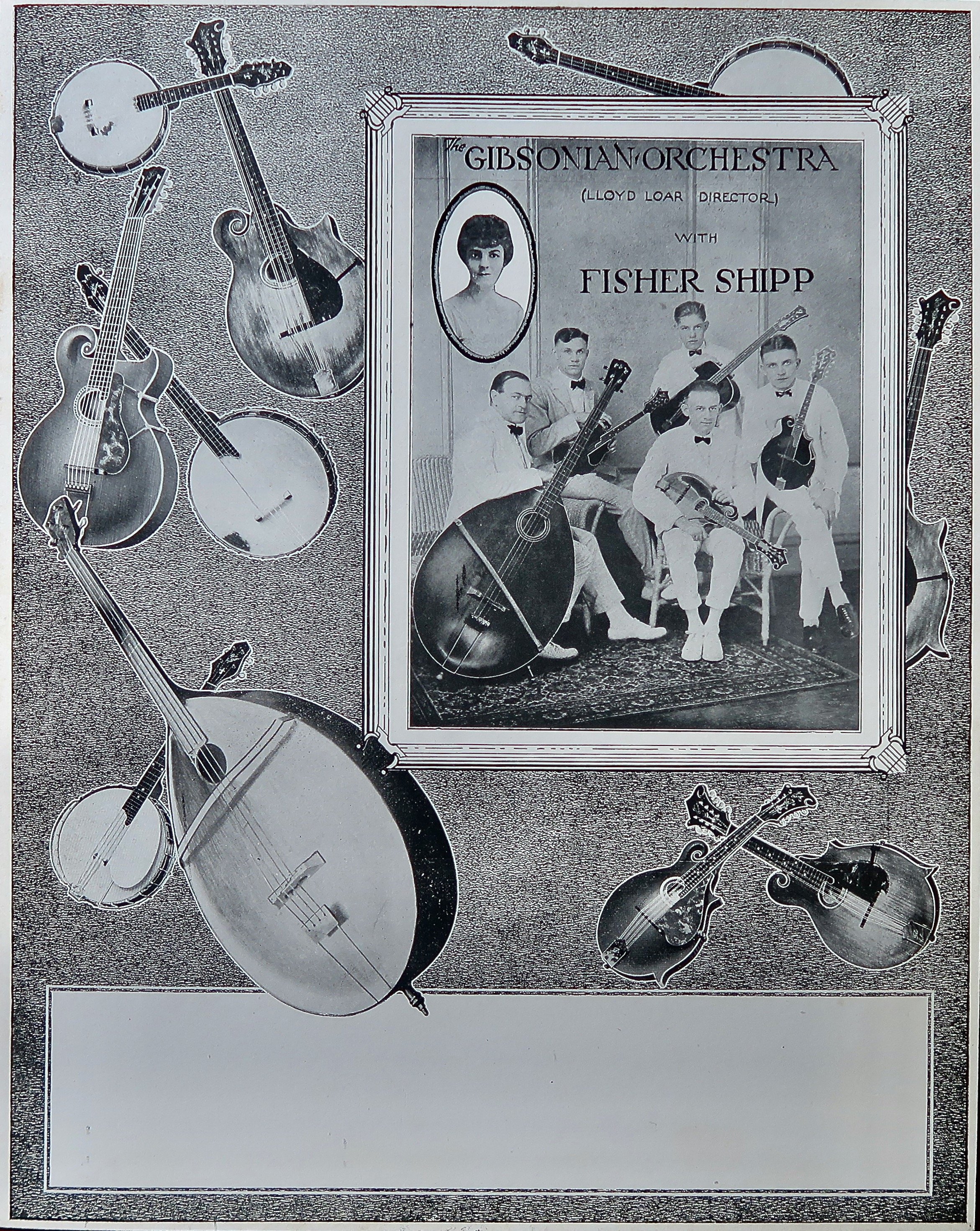

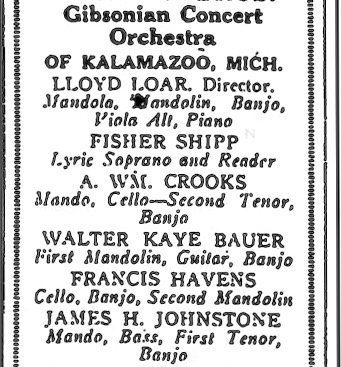

Scan of an original unused poster for the Gibsonian Concert Orchestra created for the 1922 summer tour. This poster may have been reprinted and used for the Gibsonian tours in 1923 and 1924 even though personnel changed each year.

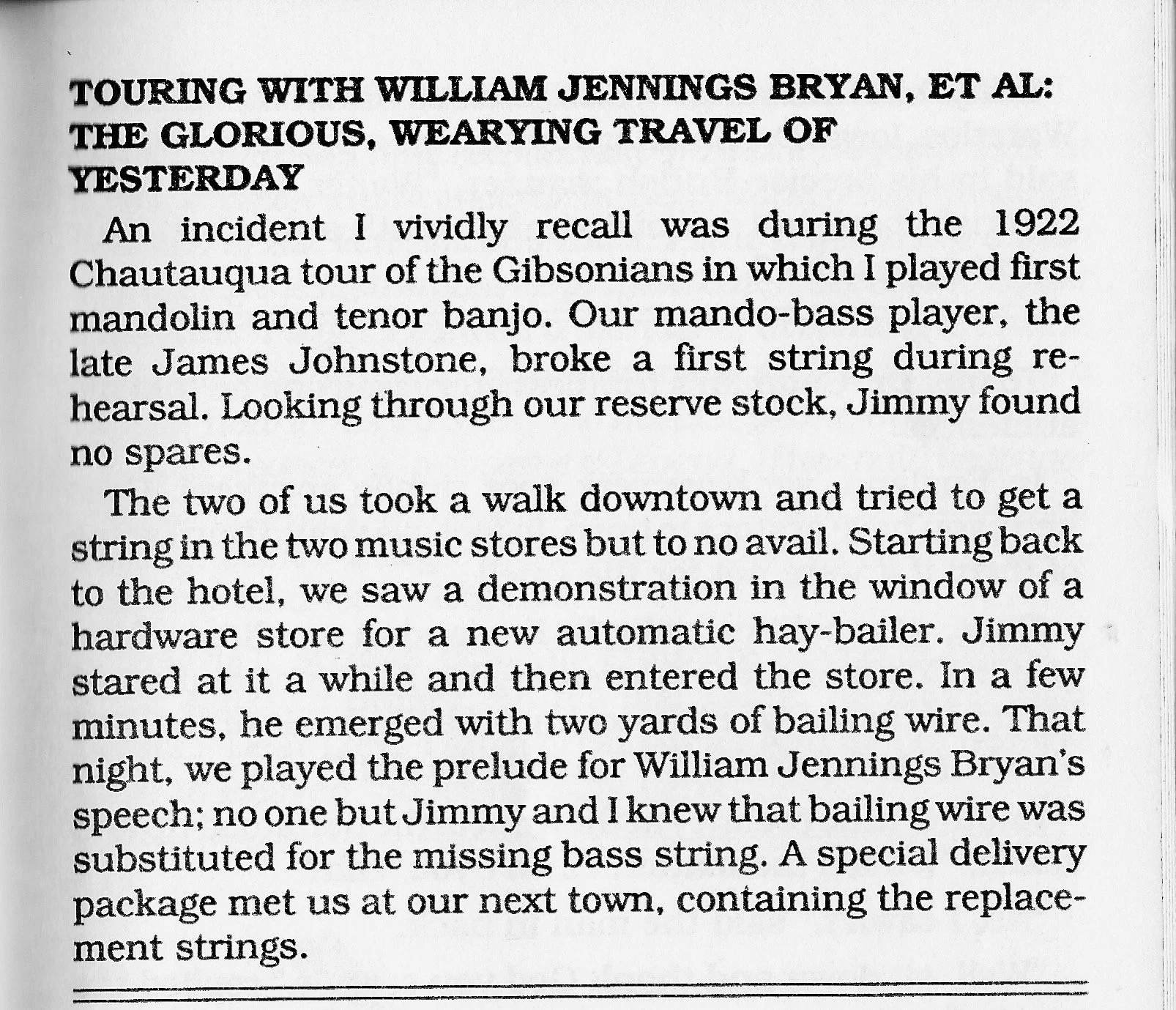

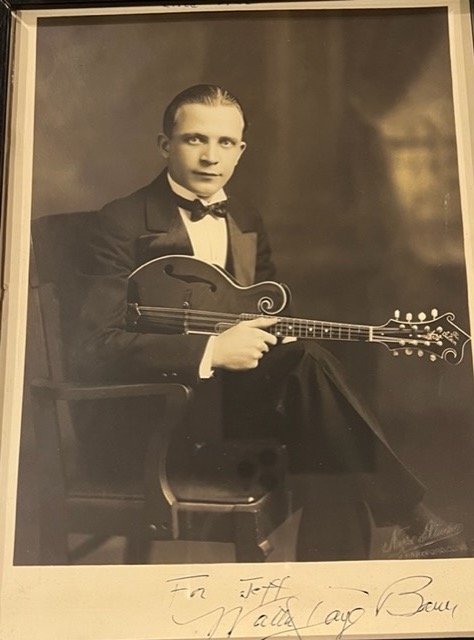

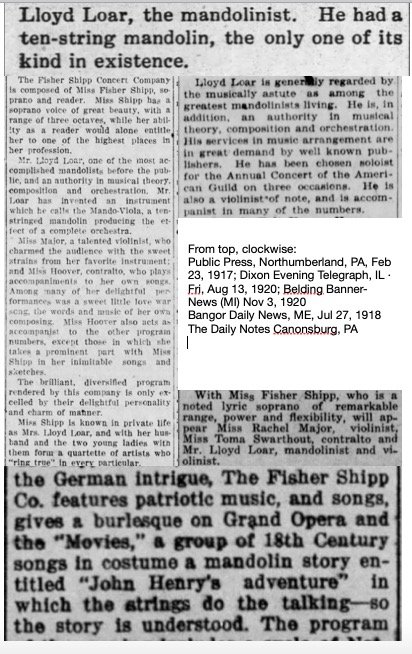

The Gibsonians were hailed as “…one of the biggest successes of the entire Chautauqua circuit and it is estimated that over 20,000 people witnessed the 105 performances given during the summer.” (Music Trades Review, October, 1922). With Walter Kaye Bauer, first mandolin, tenor banjo; William Arthur Crookes, mando-cello and cello-banjo; Francis Havens, mandolin and mandolin-banjo; and James H. “Jazz” Johnstone on mando-bass and tenor banjo; the director of the ensemble, Lloyd A. Loar performed on mandolin-viola, mandolin-banjo, viola and the carpenter’s saw; and of course, the star of the show, Fisher Shipp, privately known as Mrs. Lloyd Loar. During that summer of 1922, the Gibsonian Concert Orchestra “toured Missouri, Illinois, Kansas, South Dakota, Iowa, Michigan, and parts of southern Canada… on the same Chautauqua circuit with William Jennings Bryan, Thomas R. Marshall (former US vice-president), humorist Strickland W. Gilliam and Dr. S. Parker Cadman…” (Hartford Courant, October 28, 1922, p. 14).

The Gibsonian Concert Orchestra at Grinnell’s Music Store, Detroit, Michigan, September 1, 1922.. (Music Trades, October, 1922)

As we have seen in the previous episode, the combination concert/broadcast at Grinnell’s Music Store and Radio WWJ in Detroit, Michigan, was a successful sales technique, and both Gibson and their various affiliated merchandisers announced their intention to continue such promotions. However, for successive events, the original group from September 1 was replaced with the delightful “Gibson Melody Maids.” Mostly unmarried and in their twenties, the “Maids” were individually identified in the City Directory as stenographers at Gibson. Among their group were Nell VerCies and Dorothy Campbell, who would later join Loar’s quintet. Whereas earlier that year, Loar had performed with them and had been their coach and arranger, this autumn C. V. Buttleman took over management, and his wife Eulalia, a noted pianist, served as chaperone and musical director. Their first appearance on September 12 at Grinnell’s was reported in the Music Trades as a big success. Buttleman made plans for the Maids to tour music stores throughout the autumn.

The Gibson Melody Maids, top, with banjos, Music Trades, November 11, 1922; with mandolins, Music Trades, November 18, 1922.

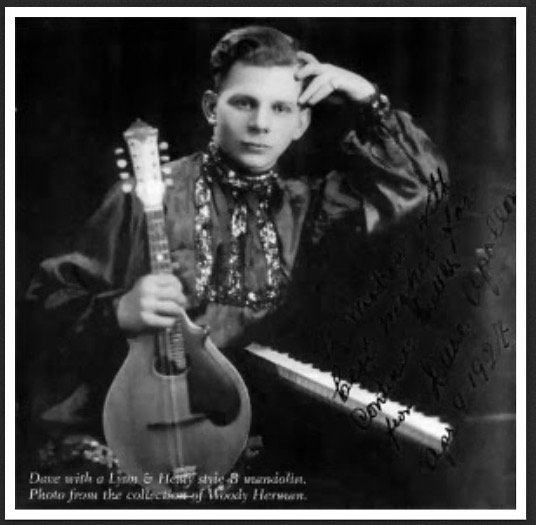

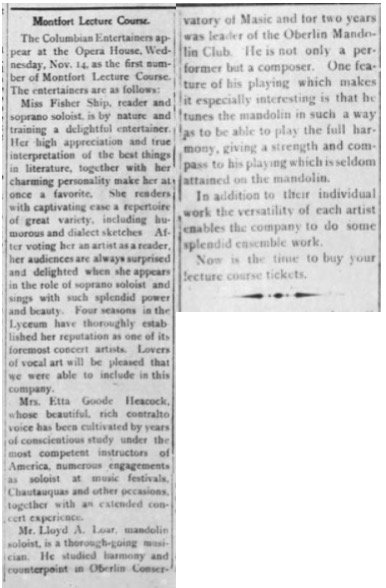

Would there be another edition of the Gibsonians? On July 26, when Loar played Davenport and Muscatine, Iowa, he took the opportunity to spend time with multi-instrumentalist, orchestra leader and Gibson artist/teacher/agent Charles A. Templeton. Loar had met Templeton at the Guild Convention earlier that year and was already aware that he had organized an orchestra of over thirty members in Sioux City, Iowa, and that his quintet, which featured his family members, had achieved local notoriety. Young daughter Hazel, especially, drew considerable attention with her skill on the Lyon & Healy Harp. Loar was also impressed with another Sioux City musician just out of high school, Marguerite Lichti, with her “kind heart and quiet manner.” Miss Lichti excelled on guitar as well as mandola. In November, Loar announced that the Gibsonians would invite Charles and Hazel Templeton and Marguerite Lichti to join Johnstone, Fisher Shipp and himself for the next summer season. He announced that the harp would be an intriguing edition to the ensemble, and that they had been invited to perform at the 1923 American Guild Convention, to be held April 21- 25 in Washington, D.C.

Top: Sioux City Journal, Sioux City, Iowa, November 19, 1922. Bottom: Charles A Templeton, first mandolin; Margaret Templeton, second mandolin; Marguerite Licthi, mandola; Mrs. C. A. Templeton, mandocello; Hazel Templeton, harp. The Crescendo, May, 1922.

What happened to the 1922 Gibsonians?

Walter Kaye Bauer and Arthur William Crookes returned to Hartford where their music institute was flourishing. The Hartford Mandolin Orchestra began performing again almost immediately, and Bauer and Crookes took advantage of the accolades they had received during the summer tour and billed themselves “The Gibsonians Society Orchestra.”

Hartford Courant, Hartford, Connecticut, Oct 28, 1922, P. 14

Francis Havens is listed in the City Directory in 1922 and 1923 simply as “draftsman,” but it is unclear if he continued to be employed by Gibson. In 1924, he is listed as draftsman for Kalamazoo Railway Company, the same company he had worked for before joining the Gibsonians. He continued to work for the Railway Company for rest of his career, and we have found no further mention of his adventures as musician. We would love to know more about Mr. Havens.

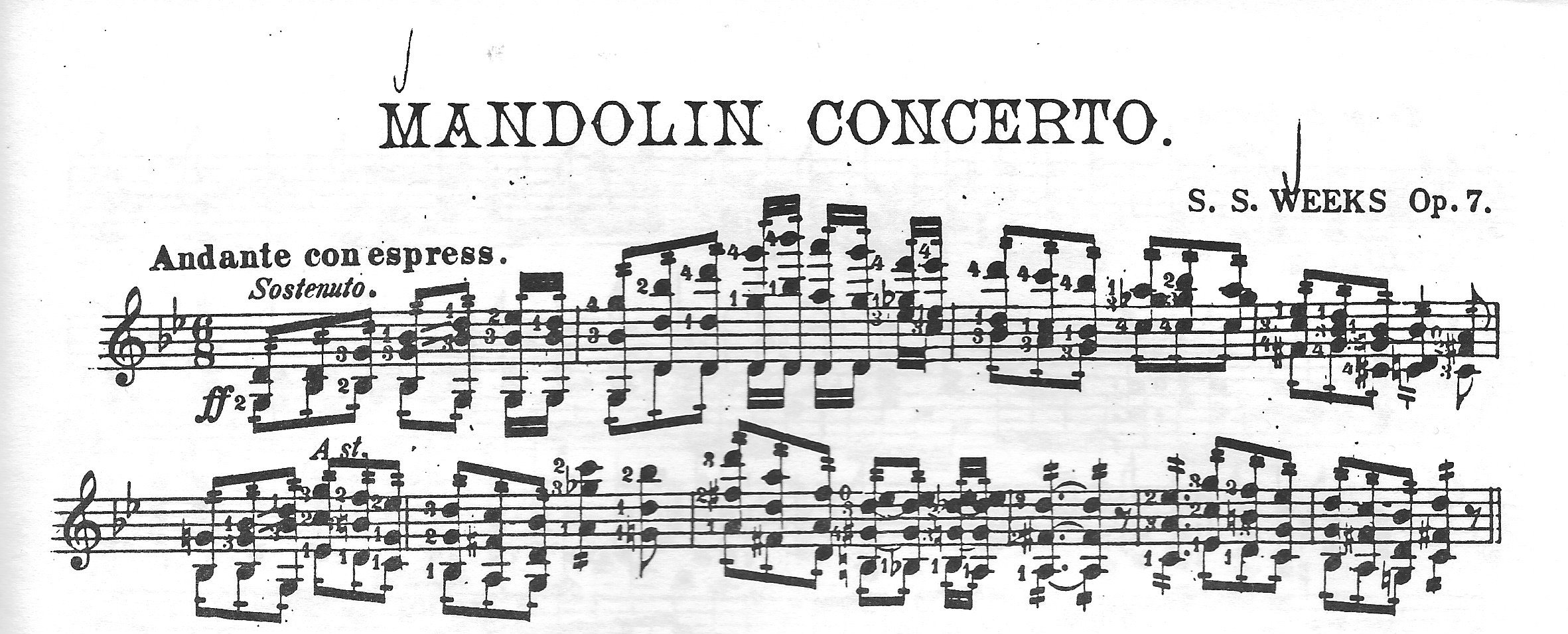

James “Jazz” Johnstone would resume his role as foreman of the stringing department at Gibson and while continuing to submit articles promoting Gibson banjos and jazz music. Johnstone, always the entrepreneur, had, in addition to his photography studio, created yet another auxiliary revenue stream: music folios. While on tour in 1921 he had offered a collection of Leora Haight’s work, and in the summer of 1922, for the price of one dollar, an aspiring musician could unlock the secrets of Loar’s mandolin solos, including the “Quartet from Rigoletto,” which had been one of the highlights of Loar’s mando-viola performance over the years. In this folio, the Quartet was transcribed for solo mandolin in standard tuning, and for those with enough strength and stretch in their fingers, all four parts could be played at once. Sales were brisk, and perhaps Loar gained some insight into the value of such publications, which would shape his career significantly after leaving Kalamazoo in 1925.

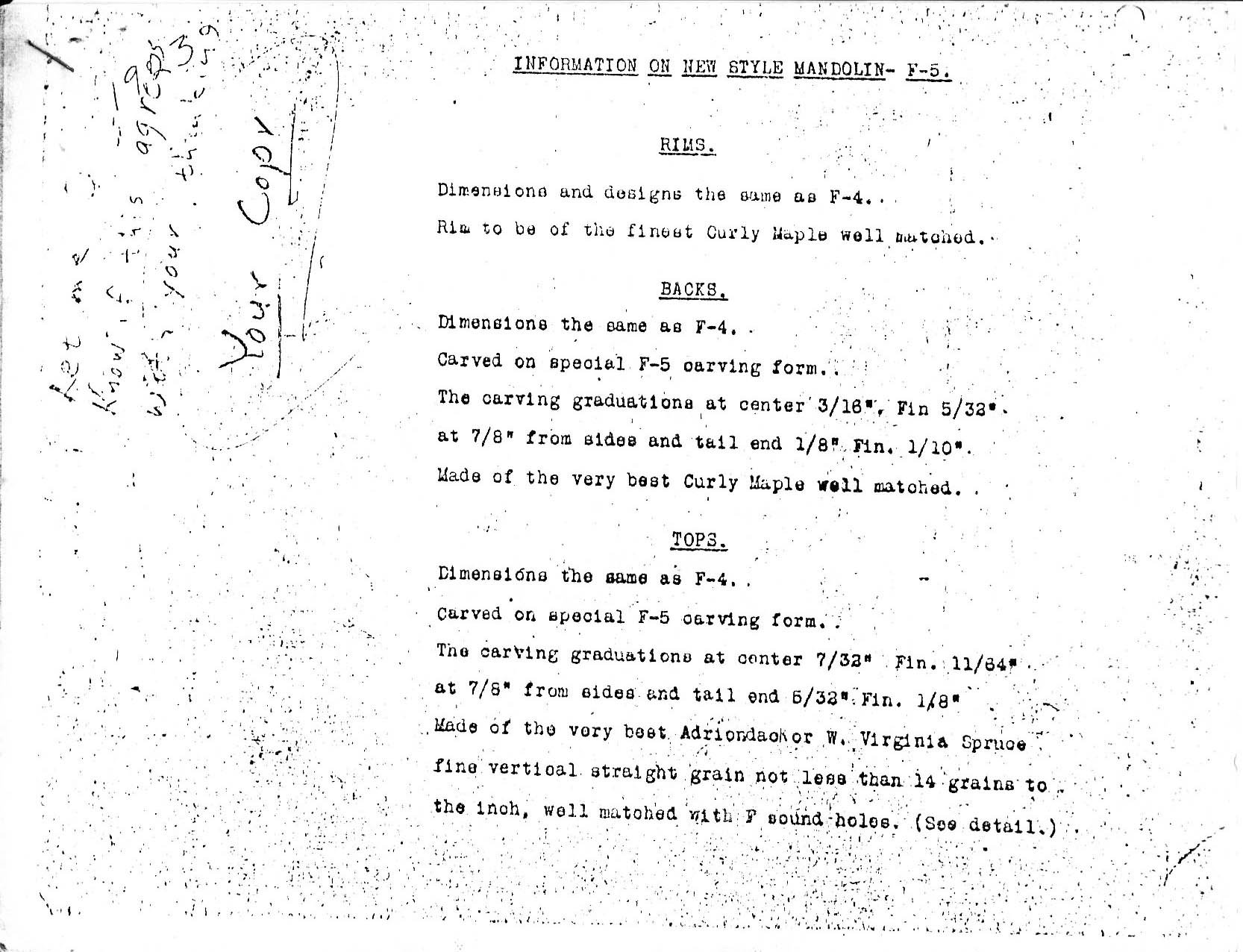

By Labor Day, Lloyd Loar had returned to his residence at the boarding house in Kalamazoo (in the City Directory in both 1922 and 1923, his name was misspelled, but the listing clearly refers to him). Sallie Fisher Shipp Loar is not mentioned in the Kalamazoo directory (boarding houses always specified wives who shared rooms with male renters). The only record of her during this period seems to indicate she stayed with her mother in Brookfield, Missouri. We have found no evidence that Loar travelled away from Kalamazoo for performances again until the spring of 1923. Based on his writings, he spent his time at 225 Parsons Street focused on the improvement of the acoustics of Gibson instruments. There is evidence that feedback from his experiences during the summer tour influenced the tonal direction of the next F-5s. We also envision that public excitement and pre-orders received from the summer tour put a priority on production of the F-5.

When attempting to arrive at conclusions about these F-5s of 1922, we are very limited: the only primary resource we have is the mandolins themselves. With minimal original documentation extant, we are confined to observational data. On each F-5, there are usually two sets of numbers: one stamped, called the “Factory Order Number;” a second, usually written, the serial number. When the mandolin is completed and ready for marketing, both these numbers are covered by oval paper labels, one with date and signature and the other with model and serial number. When these paper labels are intact and original, they contribute to proof of authenticity, so no respectable luthier would remove them to take a peek beneath. Thus, we rarely know the FON of an F-5. We assume that these numbers are basically sequential, or at least intended to be so. I hope the reader will understand that we are looking through a glass darkly here, and will accept the following conjectures as just that: possible conclusions based on observation of these data.

Top: Back of Gibson F-5 70281 with labels intact (photo courtesy Steve Gilchrist); Bottom: Back of Gibson F-5 71634 with stamp and written number. Photo by Randy Wood during a restoration.

Fortunately, we do have two FONs from 1922 F-5s (in addition to Loar’s MV-5, which did not receive the paper label that would have covered the FON). There are also two groups of serial numbers, and these two groups probably correlate to the two FONS. Our assumption about the numerical sequence of serial numbers is supported by the unique appointments characteristic within the batches, or at least of instruments examined that appear to be factory original. From the earliest production batch, FON 11609 (found in F-5 71069 signed and dated November 28, 1922), there are ten mandolins we know to be extant. Like F-5 70281 that was signed on June 1, 1922, all but one has the neck constructed in three pieces (F-5 71060 is the first known 1-pc neck). Of those ten mandolins, the “Parrot F-5, #71055,” (so-called because of aftermarket adornments which helped it garner national attention at Mandolin Brothers of Staten Island, New York, in September of 2000) is the most famous. There are others in more pristine original condition. Since Loar’s personal MV-5 has the batch number 11729 and, as we have shown, it was on tour during the summer of 1922, if these numbers are sequential, the Parrot Loar and its bench-mates were under construction or even finished well before the summer tour. It is even possible that Loar and company had more than the two F-5s to try out that summer. The signature date on the 10 mandolins from batch 11609 is November 28, 1922, but as we have shown with the first K-5, it is not unusual for there to be a significant time gap between construction and signature.

The later batch number from 1922 is FON 11739. There are five mandolins we have seen that were most likely from this batch, and the ones that survived with original features intact all have a distinctive sound: intense focus, remarkable projection and overall balance of tone and power that is quite stunning. In our opinion F-5s #71633, 71634 and 71635 exhibit this remarkable projection and clarity. In #71634, the words written in pencil “thin here” on the back indicates an effort to shape tonal characteristics during construction. Other changes initiated with this batch include one-piece maple neck, slab-cut. After spending the summer performing acoustically in a tent to audiences that often numbered in the thousands, it seems likely that Loar would have issued a mandate to increase projection. We submit the possibility that these instruments were constructed with that in mind during the period after the tour and prior to their signature date of December 10, 1922.

Gibson F-5 #71633, signed by Lloyd Loar December 10, 1922, can be heard on Tony Williamson’s solo recording of individual F-5s called “Lloyd Loar Mandolins.”

David Grisman plays 71635, named “Crusher” by Steve Gilchrist. Left to Right: Tony Williamson with fern, David Grisman with Crusher, Sam Bush with “Hoss,” and Matt Eccles with flute. Merlefest, ca. 1995. Crusher can be heard on many of Mr. Grisman’s recordings, including a two disc CD with various artists exploring its amazing sound: “Tone Poets” can be downloaded at the Acoustic Disc website.

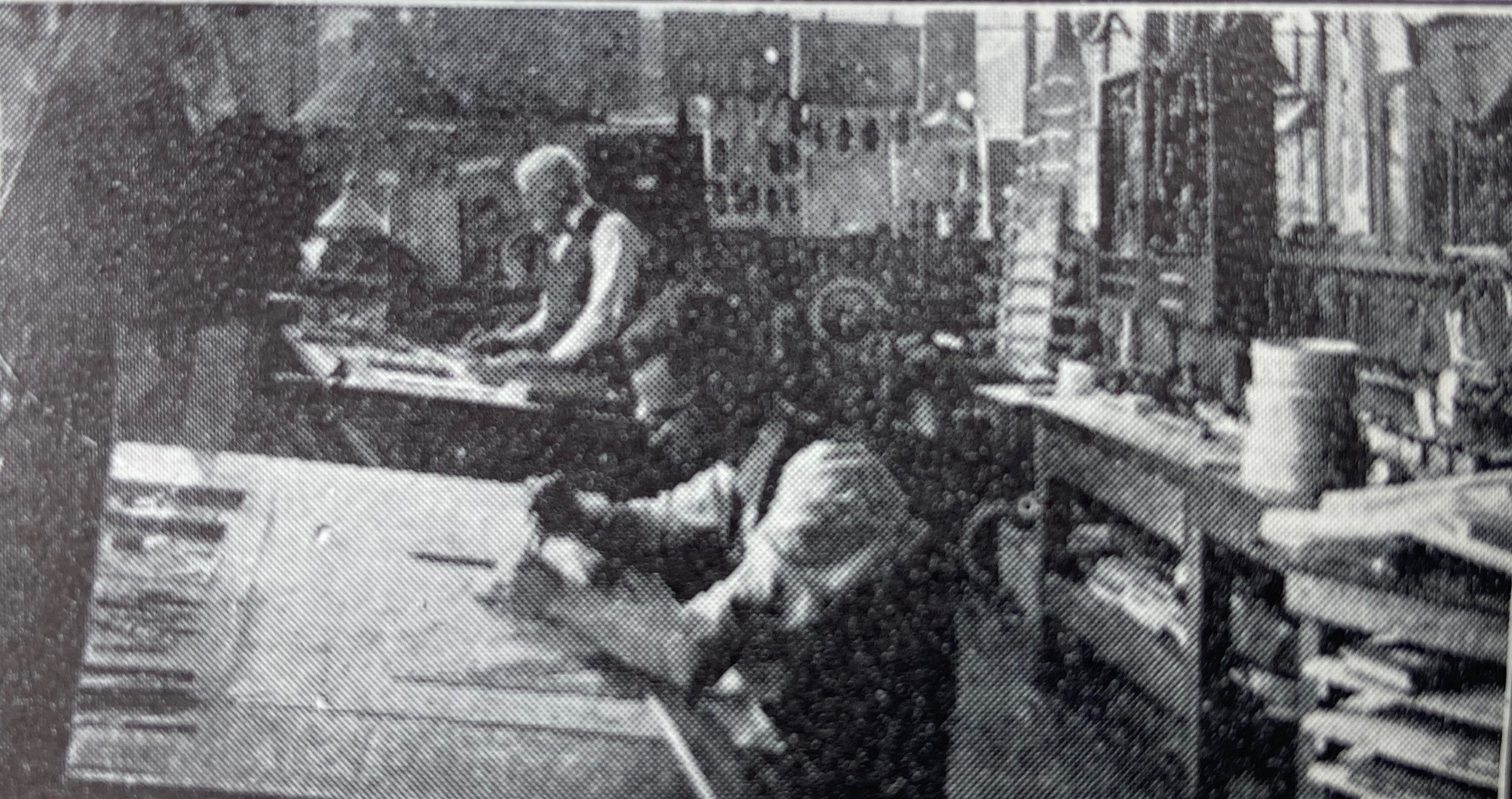

During this time, Loar also turned his eye toward the unique properties of projection accomplished with the Virzi Tone Producer. In our experience, mandolins (and violins) with a properly installed Virzi project dramatically to the back of a concert hall when played acoustically. The unusual nature of sending the sound away from the instrument has left many musicians to conclude that the Virzi weakens volume because, as they play, they do not hear it as well as a similar non-Virzi instrument. Articles by Loar exploring this phenomenon began appearing in national journals in December of 1922. He also appears with a full page endorsement in the Virzi Brothers catalogs from 1922 to 1929.

Loar at his workbench in the Gibson factory. Notice the collection of Virzi tone producers in the foreground. (Gibson catalog “N” 1923)

We now conclude Breaking News: 1922. This past year, I have pored over hundreds, maybe even thousands, of primary-source documents concerning the development of the F-5 a century ago. I have examined scores of fragile, century-old photographs, posters and music folios, often with a magnifying glass in an effort to identify specific features of the instruments. I have examined, played and studied the instruments themselves and corresponded with others who have embarked on similar missions. I must point out that even primary sources harbor pitfalls of misinformation. The Gibson catalog, for example, is an advertisers’ effort full of hyperbole, exaggeration and in some cases, outright misinformation. While it is invaluable for model numbers, prices and specifications, all data must be researched and proven before it is confirmed. The catalogs are useful for assigning dates to photos (but even a photo appearing in a 1923 catalog only tells you that the photo was taken before 1923, not necessarily current to that issue). Magazine and newspaper articles tend to be more reliable, but still must be considered from the point of view of motivation, and one must be careful of the oft-used trope of advertisement disguised as news article.

I wish to thank my faithful readers, and send gratitude to those who have replied with encouragement and/or information. I especially wish to thank our foreign correspondent, Mr. Stephen Gilchrist of Lake Gnotuck, Australia, one of the world’s premier luthiers, who so freely shared his vast experience, documents and photos from his collection, and contributed brilliant observations on appointments and construction details. I want to thank Randy Wood, who has generously given of his time, shared photos and documents from his collection and on countless occasions allowed me to watch as he performed surgery on some of these priceless mandolins. Also, thanks to Darryl Wolfe for his ongoing efforts to publish the “F-5 Journal” and with Dan Beimborn, the “Mandolin Archive;” David Grisman for his generosity in sharing music and archives; Dr. Harry Bickel for always being on call to point me to resources and enlighten me on the finer points of vintage instruments, especially Fairbanks and Vega banjos; Wayne Joyce for photos and mandolins; Dan Weinstock for sharing music and pointing me to resources; and to George Gruhn, Walter Carter and Joe Spann for their important works on the subject. A special thanks to Scott Tichenor for sharing my writings with his readers on Mandolin Cafe. Finally, I wish to thank the noted author and editor, Andrea Deyrup, MD., PhD., for casting an eye on my text and offering suggestions and corrections. She is a gifted possessor of “le mot juste.” To be clear, any mistakes, grammatical and otherwise, that remain are mine and mine alone. I will continue to look over this from time, and update the information as more facts come to light. Tony Williamson, September 20, 2022.

Tony Williamson in his shop at Mandolin Central enjoying a magnificent collection of Lloyd Loar F-5s (including 71633 and 71635), all featured in solos on the CD, “Lloyd Loar Mandolins,” .

Thank you for reading. Beginning in February 2023, we plan to celebrate the centennial of the official release of the Master Model Mandolin and follow the adventures of Lloyd Loar throughout that year. Look for full coverage here on “Breaking News: 1923.”